By Michael GersonWednesday, September 12, 2007; Page A19

There is a long American tradition of savaging failed generals, from George McClellan to William Westmoreland. It is a more novel tactic to attack a successful one. Sen. Dick Durbin accuses Gen. David Petraeus of "carefully manipulating the statistics." Sen. Harry Reid contends, "He's made a number of statements over the years that have not proven to be factual." A newspaper ad by MoveOn.org includes the taunt: "General Petraeus or General Betray Us?" --

perhaps the first time since the third grade that this distinguished commander has been subjected to this level of wit.

Gen. Andrew Jackson probably would have responded to these reflections on his honor with a series of duels. Gen. Petraeus, in the manner of the modern Army, patiently answered with a series of facts and charts showing military progress in Iraq that seemed unimaginable even six months ago.

'There is a long American tradition of savaging failed generals. It is a more novel tactic to attack a successful one.','Michael Gerson') ;

document.write( technorati.getDisplaySidebar() );

Who's Blogging?

Read what bloggers are saying about this article.

democracyarsenal.org

Don Surber

Gregory Scoblete

On Petraeus's brief watch, al-Qaeda in Iraq has suffered a major setback. It has been cleared out of the main population centers of Anbar province; its cells scattered into the countryside. The resentment of Sunni tribal leaders against al-Qaeda's highhanded brutality predated the surge -- but the surge gave those leaders the confidence and ability to oppose al-Qaeda. And this approach is showing promise among other Iraqi tribal groups as well.

In Baghdad, the Petraeus counterinsurgency strategy -- a kind of community policing with very serious firepower -- has reduced sectarian murders significantly. Some militia activity has been pushed outside Baghdad or gone underground -- and this is also a victory of sorts, because order in Iraq's capital has great symbolic and practical importance.

But for opponents of the war, such progress is beside the point. Anything less than perfection in reaching a series of benchmarks is evidence of failure and reason for retreat. Former senator John Edwards, bobbing like a cork on every current of the left, calls for "No timeline, no funding. No excuses" -- a sudden cutoff of resources for American combat troops. Other critics recommend that American forces withdraw into a noncombat, supportive role, with a "small footprint," while unprepared Iraqis are pushed into the lead -- exactly the strategy that led to the escalation of violence in 2006.

These are not serious options. But the administration does face a serious question: Even if this military progress continues, how does it lead to the endgame of American withdrawal instead of Iraqi dependence? In spite of recent gains, civilian casualties remain high, sectarian groups are still deeply at odds, and the central government remains corrupt and ineffective.

Administration officials answer that they are seeing a promising, bottom-up change in Iraq -- something organic, not imposed or designed. Instead of national, political agreement, Iraq is experiencing local, tribal reconciliation. Even without a national oil law, oil revenue is being shared. Even in the absence of a de-Baathification law, tens of thousands of former Baathists are getting their pensions. Grass-roots progress, the argument goes, will eventually produce more responsible, pragmatic political leaders -- Sunnis who oppose al-Qaeda and Shiites who fight Iranian influence -- as well as more capable and professional Iraqi military forces. And this would allow America to provide the same level of security with fewer and fewer troops.

Petraeus's recommendation of troop reductions beginning in December, with a return to pre-surge troop levels by summer, is a down payment on this expectation.

But future reductions, he made clear, will be based on conditions in Iraq, not timelines. And those conditions are hard to predict.

At least three factors could complicate future withdrawals:

First, as the British leave, Basra and the south could descend into a chaos of battling militias -- threatening Iraqi oil fields and American supply lines. Would U.S. troops be forced to intervene?

Second, Iran may not tamely accept American progress in Iraq. Its government is already involved in the training and arming of proxies in Iraq. How would America need to respond if the Iranians escalate further and provide, for example, surface-to-air missiles to militias?

Third, even if Iranian-backed groups are isolated and undermined, the regular Shiite militias, often infiltrated into the police and Interior Ministry, are still forcing Sunnis out of mixed neighborhoods in Baghdad. What needs to be done to stop them?

Despite real military progress, the situation in Iraq remains difficult. Gen. Petraeus is a skilled leader, but we do not know if even he can win. We know, however, one thing: If he is slandered, his advice is dismissed and Congress cuts off funding for the troops he commands, defeat in Iraq will be certain.

michaelgerson@cfr.org

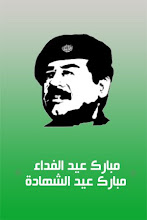

The Iraqi Resistance Web site is:An independent media source about the biggest crime of 21st Century. it's One person's effort to correct the distorted perceptions provided by commercial media.(CNN, FOX, ABc etc) This web site grew out of my personal frustration and anger at the failure of traditional commercial media to inform the American public, especially as it relates to Iraq.

Blog Archive

-

►

2011

(1)

- ► March 2011 (1)

-

►

2010

(6)

- ► December 2010 (2)

- ► September 2010 (1)

- ► April 2010 (1)

-

►

2009

(13)

- ► December 2009 (2)

- ► September 2009 (1)

- ► August 2009 (1)

- ► April 2009 (1)

- ► January 2009 (6)

-

►

2008

(10)

- ► December 2008 (3)

- ► November 2008 (1)

- ► March 2008 (2)

- ► January 2008 (4)

-

▼

2007

(78)

- ► December 2007 (8)

- ► November 2007 (7)

- ► October 2007 (10)

- ▼ September 2007 (10)

- ► August 2007 (7)

- ► April 2007 (7)

- ► March 2007 (4)

- ► February 2007 (5)

- ► January 2007 (2)

-

►

2006

(70)

- ► December 2006 (5)

- ► November 2006 (6)

- ► October 2006 (9)

- ► September 2006 (4)

- ► August 2006 (9)

- ► April 2006 (5)

- ► March 2006 (11)

- ► February 2006 (9)

- ► January 2006 (2)

No comments:

Post a Comment